What is Marxism and Critical Theory? Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) Dublin, Saturday, May 25th

May 22, 2013 § Leave a comment

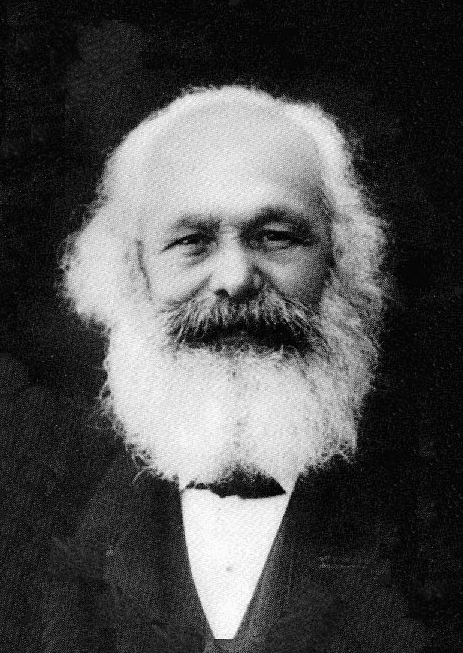

What is Marxism and Critical Theory?

Lecture Room, Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) Off-Site at NCH,

Saturday, May 25

Talk: 12:00noon – 1:00pm | What is Marxism and Critical Theory? An Introduction to Marxism and Critical Theory, presented by Declan Long and Francis Halsall, Lecturers, MA Art in the Contemporary World, NCAD.

Panel Discussion: 1.00pm – 2.00pm | Panelists include: Mark Curran (artist and educator), John Molyneux (socialist and activist blogger on Marxist theory and art), Declan Long and Francis Halsall, (Lecturers ACW, NCAD). This panel discussion considers the renewed interest in Marxist theory and its manifestations and relevance for contemporary art theory and practice. This discussion will draw on some of the central ideas addressed in the Intelligence Squared debate, Karl Marx was Right to be screened afterwards. To engage with the content of discussion we advise attendees to view this debate in advance. Please see details below.

Screening: 2.00pm – 3:45pm | Karl Marx was Right

A debate from Intelligence Squared titled Karl Marx was Right, broadcast on Tuesday 9 April 2013 can be viewed below

Booking is essential. Free tickets are available here.

No Longer Indifferent: The Photography of Milton Rogovin

May 1, 2013 § 6 Comments

He is dangerous to the internal security because of his strong adherence to Marxist-Leninist principles (internal FBI memo dated April 8, 1968)

In 1909, five years after Lewis Hine had made his first journey to Ellis Island to document mass migration, another American photographer, Milton Rogovin, was born in New York City. The son of Jewish migrants, he would, like Hine, have another career before making photographs, experiencing a significant upheaval in his life when everything would change. Having graduated from Columbia University and subsequently practicing as an optometrist, Rogovin moved to Buffalo, upstate New York in the 1930s. This was at the height of the Great Depression, and coupled with living in an area defined as socially deprived, Rogovin became politically active. As he comments; ‘this catastrophe had a profound effect on my thinking, on my relationship to other people. No longer could I be indifferent to the problems of people’ (1974: 12).

He became an outspoken critic of government social policies and became involved in the establishment of a union of optometrists and optical workers. He subsequently volunteered with the local branch of the communist party, a decision which would result in a call in 1957 to appear before Senator Joseph McCarthy’s travelling House Committee on Un-American Activites. In this era of Cold-War politics, such an appearance would cost him and his family their livelihood but would ultimately change the course of his life. Rogovin had an existing interest in photography, which he recalls in a radio interview:

When the McCarthy committee got after me, my practice kind of fell pretty low…my voice was essentially silenced, so I thought that by photographing people…I would be able to speak out about the problems of people, this time through photography*.

Influenced through his friendships with the photographers Minor White and Paul Strand, he would subsequently photograph in many countries around the world, from Mexico and Chile to Zimbabwe, always drawn to critically addressing social and political-based issues. Concerned with all forms of disenfranchisement, but primarily the role of labour, he quotes directly the words of the German artist Kathe Kollwitz to describe this motivation:

My real motive for choosing my subjects almost exclusively from the life of the workers was that only such subjects gave in a direct and unqualified way what I felt to be beautiful…Middle-class people held no appeal for me at all. Bourgeois life as a whole seemed to me pedantic…much later on, when I became acquainted with the difficulties and tragedies underlying proletarian life…I was gripped by the full force of the proletarian’s fate. (1974: 12)

Rogovin’s reasons may appear somewhat dated and naïve even politically incorrect in terms of contemporary discourse surrounding class, but the motivation to photograph those who he described as ‘the forgotten ones’ (ibid.: 12) underlines his profound sense of social and political responsibility to bring critical attention to both their situation and the circumstances.

From the 1970s, Rogovin began to focus on his home borough of Buffalo and its inhabitants – a survey of miners and their families, steelworkers before and after plant closings, Native Americans on reservations in the state and a local Yemeni community, among others. The work lies within a humanist documentary tradition, evidenced in part by his application of black and white film, long associated with and evoking traditional photojournalism and reportage. However, what distinguishes Rogovin’s visual approach is his consistant and primary use of the portrait**. Acknowledging the work of Hine (Rogovin 1974) as an inspiration, many of the subjects within his images present themselves to the camera, facing forward looking and straight into the camera. As Rogovin describes:

I always asked permission before taking pictures. I wanted to get close and make people be the most important thing in the frame. I never directed them or told them how to stand, how to hold their hands, or what to wear. The only thing I asked them was to look at the camera. I liked it when I saw their eyes and that’s when I knew I was ready to make their picture. Typically, I would make 2 or 3 exposures. When you look at these pictures, you know there was no monkey business, and that I was not sneaking around trying to steal pictures of people. (Hirsch 2004: 8)

Describing the process of gaining the trust of the individuals he photographed, Rogovin draws attention to an understanding concerning the role of visibility and, as a result, the necessity for trust and the significance of complicity:

At first I was regarded with great suspicion, people thought the authorities sent me to spy on them.…[In] those days, people in such areas were not used to being photographed, or indeed being given any attention at all. I showed an interest, was polite, and tried to put people at ease…I would come back and give anyone I photographed a copy of their picture a few weeks later. Gradually I became known and trusted, and eventually people began to ask if I would take their picture. I remained in the area for the next three years. (Hirsch 2004: 7)

Rogovin added time to this process, in the form of long-term relationships, revisiting individuals and their families, which became an integral and critical aspect of his practice. He produced portraits, therefore, that I would describe as ‘over time’ – transcending time and must be therefore viewed simultaneously as both a singular experience but also beyond that singular experience one usually associates with the photographic encounter. In the images above, for example, the Rodriguez’s (images above and below), a couple and their family who lived not far from Rogovin, were first photographed in 1974, continuing to do so until 2002. Images such as these speak powerfully not only of the relationships and lives lived between the subjects portrayed but also of their intimate relationship with the photographer:

In Rogovin’s work the subject of each photograph, commands equal strength. Whether because of his respect and empathy for his sitters or the sincerity of his humanism and politics, this seemingly simple concept re-addresses the delicate balance of power between the observer and the observed.***

This innovative and critical use of the portrait was extended in 1993, when in collaboration with the anthropologist Michael Frisch, they published the book Portraits in Steel. The modern world that Hine had previously documented was becoming the so-termed ‘post-industrial’ landscape of the late twentieth century. Rogovin had begun in the 1970s to make a series of portraits of workers in the steel foundries in Buffalo. As the American steel industry collapsed amidst the increasingly globalised market of the 1980s and the once ‘Steel Belt’ was transformed into the now termed, ‘Rust Belt’, he returned along with Frisch to document this change. The result was a monograph, where portraits spanning almost 15 years appeared alongside the extended narrative of the testimonies gathered by Frisch. One continues to sense the relationship established with Rogovin in the apparent openness of the individuals taking part. Without such complicity, such a project could not have been undertaken.

Joseph stands (image above) shovel in hand, bare-chested with a vertical scar. The obvious use of flash highlights it as an environment usually lit only by the fires of the furnace. Here in in the steel mill at Bethlehem, Rogovin provides the transparent means with which the physical nature of this particular form of labour is revealed. Joseph is complicit in this undertaking in his stance and thereby completes the two-dimensional part of this meaning process. Now, the final completion of meaning will be undertaken by, and involve the complicity of, the viewer. Originally from the southern United States, Joseph grew up on a farm, and was two years short of service at the mill when he lost a leg to medical complications. This resulted in him never receiving a company disability pension and shortly after his operation the mill closed. He remains stoic in his advice for future working generations:

Well, the only thing I can tell them: get you some education, try to learn you a skill, because you will never see this industrial movement no more…that’s the reason I say the future is, they won’t be using their muscles, they’ll be using their brain (Rogovin and Frisch 1993: 312-313)

A significant undertaking, Portraits in Steel provides an extended visual and oral engagement with a changed industrial environment. The monograph is now a document to those who gave. In his discussion of the role of images and text, Rogovin’s collaborator on the project, Frisch writes:

[T]he book proceeds from a belief that all portraiture involves, at its heart, a presentation of self. It also does not deny that artifice, interpretation and even manipulation are necessarily involved in arranging the portrait session, rendering the images presented, and conveying them to others in some form or other.…[But] portraits do represent and express a collaboration of their own between subject and image maker, a collaboration in which the subject is anything but mute or powerless, a mere object of study…Stories given, rather than taken. (ibid.: 2-3)

In 2003, a short documentary titled Milton Rogovin The Forgotten Ones by the filmmaker, Harvey Wang, was released. A celebration of the work of Rogovin, the film provides insight into the long-term relationships formed by the photographer and those he sought to portray.

In January 2011, Milton Rogovin passed away in Buffalo, New York, one month after celebrating his 101st birthday.

Sources:

*As described by Milton Rogovin from an interview, ‘Milton Rogovin, Photographing “The Forgotten Ones”’ (2003), National Public Radio (NPR), broadcast 14 June 2003. Available here.

**Significantly, Rogovin’s application of the portrait, was described by his collaborator, the Anthropologist, Michael Frisch, as ‘pictures given, rather than taken’ (1993: 3).

***Quote from press release that accompanied the exhibition, ‘Milton Rogovin: Buffalo’ (Danziger Projects Gallery, New York, USA, October 20 – November 24 2007). Available here.

Texts:

Hirsch, R. (2004) ‘Milton Rogovin: an activist photographer’, Afterimage, September/October, 3–7.

Rogovin, M. (1974) ‘Six Blocks Square’, Image, Vol. 17/2, 10–22.

Rogovin, M. & Frisch, M. (1993) Portraits in Steel, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

A version of this text was included as part of my practice-led doctorate thesis, the abstract of which can be viewed here and here (scroll down).